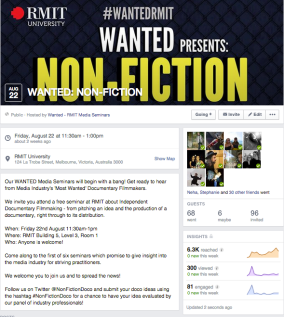

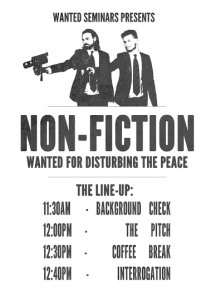

The series of RMIT WANTED Seminars was kick-started with the NON-FICTION Seminar organised by myself and 11 other aspiring documentary filmmakers studying Media at RMIT. Being the first of the 6 seminars, we had to complete a huge amount of work in an extremely short amount of time – less than 3 weeks to be exact. For this reason, I haven’t been able to post updates about the progress of the seminar preparations as they occurred, and instead I will be writing this one blog post which encompasses my whole experience from the preliminary organisations right through to post-production of the event.

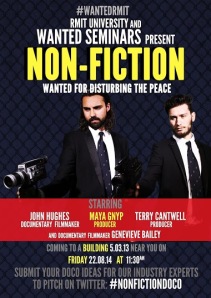

Our first meeting as a group took place during class time and everybody attended. We took this time to organise the large group of 12 into smaller, more focussed groups. We had a team of producers; a team of promoters; and finally a technical team. Greta Robenstone, Adam Ricco and myself formed the team in charge of marketing and promoting the seminar. We discussed the requirements of this responsibility amongst ourselves and decided that Adam would make name-tags, Greta would design the poster, and I would make the promotional video.

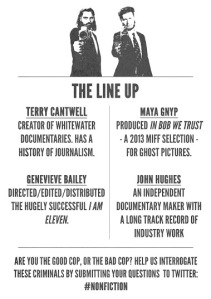

I edited together a short promotional video for the seminar from footage of Zac and Adam shot by Greta against a green screen. This was my first attempt at editing using Keylight in order to remove the green screen and replace it with a chosen background. I pushed myself in order to achieve a desired effect and it worked quite well – I definitely will be using this technique again in the future. Greta and I ensured that we used the same fonts and colour schemes decided upon by the steering committee so that our seminar material would look cohesive. I ensured that the video was kept to a minimal length (30 seconds) because it was created to be viewed quickly on various different social media platforms. It grabs the attention of viewers with bold fonts and loud colours displaying the main elements we wanted to communication, such as date, time, location and guests. We also ensured that the themes of Pulp Fiction and filmmaking were clearly featured through the imagery. View the video below:

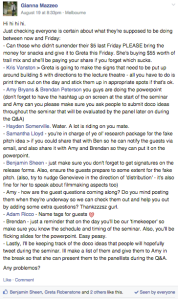

Between this meeting and the next meeting, not a lot of work had been done. We only had one guest secured and time was ticking away. This made it really difficult for the promotional group to start getting the word out about our seminar because we had no guests to feature on the posters and in the video. Thus, when we all met again the following Friday afternoon during class time, we really had to stress the importance of everybody being 100% on top of their tasks. During this meeting, everybody was delegated very specific roles to ensure that everything would be completed in time for the seminar. I acted as a scribe during meetings, writing down every role we decided upon and who would be carrying out what task. As the week went by, I would post everybody’s roles on the Facebook group and ensure that everybody was being reminded to complete their jobs. Although this was a tedious process and I may have come across as controlling or a bit of a pain – I felt as though this process was necessary as people were becoming quite slack and forgetting how quickly our seminar was approaching. This approach to delegation and organisation of the group seemed to work quite well, as everybody could be held accountable for their agreed upon responsibilities.

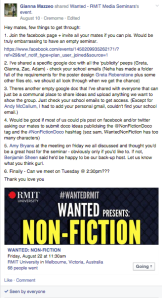

I also created a @NonFictionDoco Twitter page as well as encouraging the use of the #NonFictionDoco hashtag. Furthermore, I took it upon myself to manage the Facebook event for the seminar that was initially created by the steering committee. I was the only group member to invite people from my personal Facebook account to the seminar. I believe that this really helped to involve the broader community in our seminar rather than just restricting our audience to RMIT students only. Furthermore, even if they didn’t actually attend the seminar, their ‘cyber attendance’ would’ve made the Facebook event far more visible to a larger amount of people who weren’t necessarily invited.

Expanding upon the use of social media to gain more public support and involvement, I came up with an idea to involve potential audience members. This involved the public tweeting ideas for a documentary that they would like to have critiqued by our panel of industry professionals. We gained a few submissions, however, we ran out of time during our seminar and could not address these ideas.

In addition, I volunteered to be the liaison between our group and the steering committee. This didn’t involve as much work as expected, perhaps because we were the first group to hold a seminar and the steering committee weren’t entirely sure of what was required. On occasion, I spoke with Ronja Moss via Facebook chat, phone calls and email in order to ensure that everything was running smoothly. Furthermore, we discussed the issue of where we were allowed to put posters up in certain areas of Building 9 along with the confusion regarding the regulation of the RMIT logo used in posters and videos.

Ronja also would ask me to alert my group of certain documentation that was due such as release forms. Further, once post-production documentation was completed and uploaded to the Google Doc, I ensured that Ronja had been notified of its completion and that the Google Doc was shared with her via her student email.

Finally, the last of my roles entailed a promotional chalk drawing on Bowen St to lure in any strays on the road with a couple of hours to kill between classes. This was a final attempt to draw in the last few audience members on the day and was drawn about 2 hours prior to the seminar.

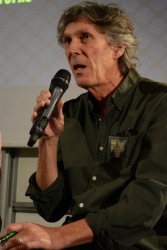

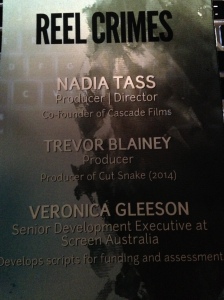

After this hugely demanding process and such a small amount of time to pull something decent together – our seminar went unexpectedly well! The guests all arrived on time; there was food and drinks available; the lighting, sound and camera setup worked seamlessly; and everybody seemed to be quite engaged by our panel of guests.

Personally, I believe each and every one of our guests were hugely insightful. I learnt a lot about documentary filmmaking and the persistence involved in becoming successful in this industry. I noticed that many of the panellists did not care much for money, and I believe that most documentary filmmakers would expect, to some extent, to be making a minimal profit in order to make films that they are passionate about. To me, it seems like a noble job if done appropriately and if ethics are upheld. If anything, the wise words of our panellists solidified my interest in documentary filmmaking and encouraged me further to make the kinds of films that interest me, as well as a particular kind of audience.

I believe that this seminar project as part of Media Industries 2 will provide students with endless benefits. Not only has it provided us a chance to learn more about a specific area of the media industry within which we’d like to work, but we also get to meet people whose jobs we aspire to have. Contacting industry professionals by emailing and cold-calling is definitely a technique that will be exhausted countless times throughout each of our careers. Further, meeting people we admire allows us to ask them for advice and potentially network and find out about potential future work.

Lastly, the series of seminars as a whole allows us to attend a broad range of seminars that address a variety of different topics. For example, although I chose to participate in the Non-Fiction Seminar, this doesn’t mean that I only want to make documentaries in my career. I am also interested in television, drama film and women in the media industry and will be able to find out more about these topics by attending other groups’ seminars. As attendance to 3 or more other seminars is compulsory, I believe this will benefit me greatly as I will learn about a broad scope of potential directions my career can take.

I have been greatly surprised by the standard of guests we have all been able to achieve. This goes to show that really high quality industry professionals are simply approachable, lovely people that are willing to lend a hand for people trying to break into the industry. It demonstrates that our dreams and aspirations are perhaps only a phone call or an email away. In order to get what you want – you need to get off your butt and take it!

The mark I’ll be giving myself for my contribution to the NON-FICTION Doco Seminar is an HD (85%).

You must be logged in to post a comment.